Banks Island, -the westernmost island in the Canadian arctic archipelago.

Banks Island is in general a polar desert where the tundra is frozen and snow-covered from September until June. Snow and freezing temperatures can however occur at any time of the year. It is such placed in the archipelago that does the island to be extremely weather exposed. The island is visited of only a handful or two humans a year except for the inuvialuits living at the Ikhuak (Sachs Harbour) settlement and people to visit there. Per today the settlement counts 115 residents. They are used to delays & cancellations of flights due to often unfavorable weather conditions.

Banks Island covers an area 70,028 km² and it is the world’s 24th biggest island and Canada’s fifth biggest island.

While parts of the Arctic have been inhabited for nearly 4000 years, the earliest archaeological sites found on Banks Island are Pre-Dorset cultural sites that date approximately 3500 years back.

It was not until 1850 that Europeans visited Banks Island. Robert McClure, commander of the HMS Investigator came to the area in search of the lost Franklin Expedition. The Investigator became trapped in the ice at Mercy Bay at the island’s northern end. After three winters, McClure and his crew – who were by that time dying of starvation – were found by searchers who had traveled by sledge over the ice from a ship of Sir Edward Belcher’s expedition. They hiked across the sea-ice of the strait to Belcher’s ships, which had entered the sound from the east. McClure and his crew returned to England in 1854 on one of Belcher’s ships. At the time they referred to the island as “Baring Island.”

From 1855 to 1890 the Mercy Bay area was visited by the Copper Inuit (Inuinnait) of Victoria Island to collect important raw material such as metal and wood from the abandoned ship. They also hunted Caribou and Muskox in the area as evidenced by the large number of food caches.

Leaving mainland via Cape Dalhousie on the northern tip of the Tuktoyaktuk Peninsula heading for Banks Island.

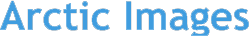

Drifting sea ice covered most of the Beaufort Sea along our route northwards.

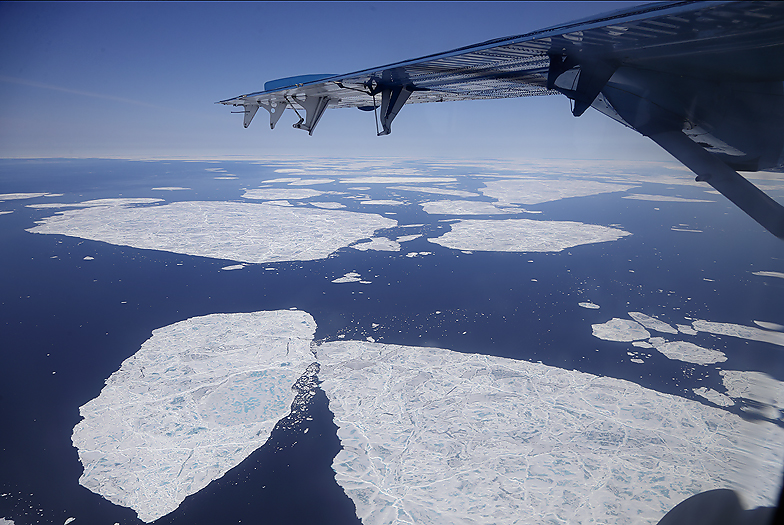

Approaching Banks Island. The winter ice still cover the sea west of the island.

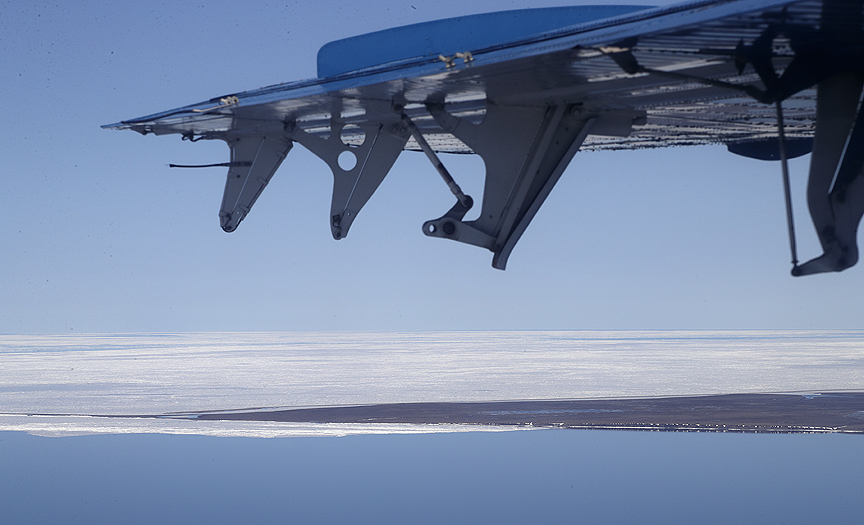

Finally at Banks Island, after a 2 hours flight from Inuvik and refueling in Sachs Harbour we continue our flight and heading northeast for the next hour. Big River below us. This is a typical meltwater river, -it is only to hope that “our” river which also is a meltwater river does not have as low water level as the Big River.

Finally on the ground in the interior of Banks Island after in total over 3 hours in the air. Pickup place after ended trip is agreed and the Twin Otter pilot says goodbye.

After the plane has left it is remarkable quiet. It is wonderful to be in the arctic again !

Now it is us few humans in a huge and magnificent landscape, the wildlife and our canoes that counts for the coming weeks.

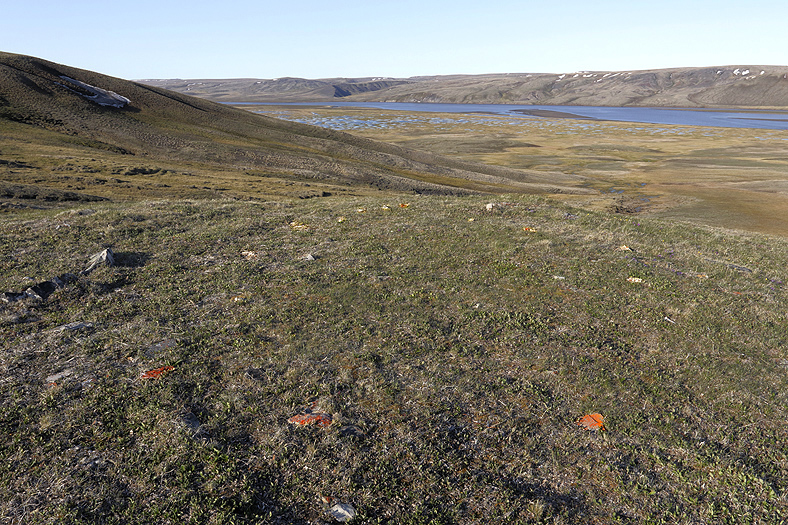

Our way of transport northwards in the Thomsen River valley, -beautiful and welcoming…! The land along the route is characterized by a broad, lush valley flanked by gently undulating hills. The eroded landscape to the northern seashore is from the Cretaceous and Devionan epochs. A big area here in this part of Banks Island was not glaciated during the last ice age. It is anticipated that this area was part of the Banksian refuge in this period.

After establishing our first camp it was time for a hike in this beautiful land. The Thomsen River valley has been used by ancient inuit cultures for thousands of years. Here remnants of a cache once filled with meat. Typical placed on a hight beside the river.

King Eider males. Many of the females are on nest at this time of the year.

Horned Lark (left) (FAY) and Lapland Longspur (right) are character species of the smaller birds here.

Canada Goose (left) and Tundra Swan (right) are character species of the big birds.

The big and exclusive Yellow-billed Loon is also rather common.

Part of camp by the Thomsen River. The weather can occasionally be rough here and it is important to use tents who can withstand continuous strong winds. Permafrost does use of tent pegs difficult some places, and self standing dome tents are recommended. Observe the Muskoxen on the hill top at the other side of the river. After setting up camp we discovered that people from the Thule Culture had done the same here between 1000 – 1500 AD (see tent ring in the foreground).

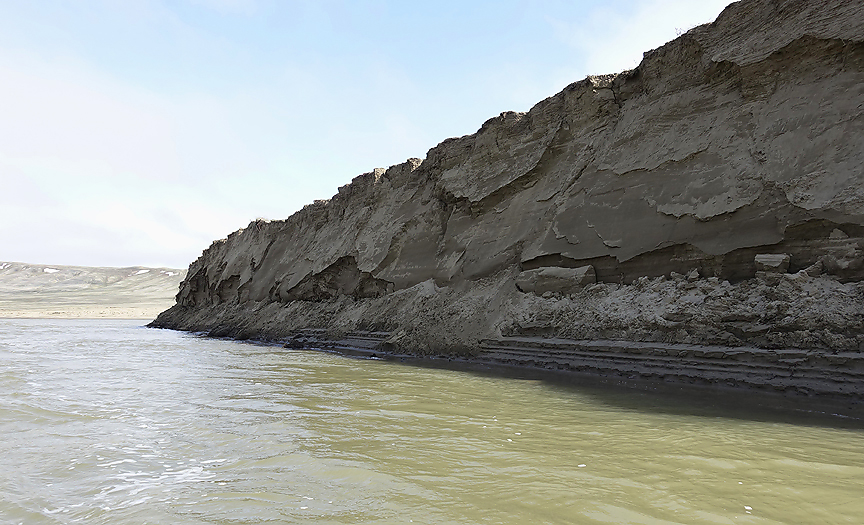

The river is silty caused by constant land erosion during the thaw up in the brief summer. Now and then we observe that small parts of the land slides into the river. It has happened that parts of Pleistocene animals (Woolly Mammoths etc) become exposed.

Total collapse of big part of land along the Muskox River (probably caused by thawing permafrost).

Pattern ground caused by permafrost (ice wedge polygons). Aerial photo.

Arctic Locoweed. Note the pingo in the background.

Woolly Louseworth (left) and Northern Jacob`s Ladder (right).

Alpine Draba (left) and Arctic Locoweed (right).

The Alpha Couple with the male in the foreground.

Curious adult male Arctic Wolf coming to check out the intruders to their territory. For more new Arctic Wolf images, -please see the Wolf gallery.

Typical for Wolf killed Muskox (as this) is that the rib bones have been chewed off close to the Spine.

Muskoxen are the main prey for the Wolves. It is typical for Wolf inhabited areas that the Muskoxen form either a line of animals close by each other, or a circle with the calves inside when the threats come from different angles (i.e. a pack of Wolves).

No Muskoxen was seen on Banks Island in the 18th century until 1952 when a Canadian biologist observed one animal at the north coast of the island. The population increased with a near unbelievable speed and counts per today around 50.000 animals here, which is about 2/3 of the global population. For more new Muskox images, -please see the Muskox gallery.

Muscox family herd.

Naquk kill-site (also called Head Hill) is a very special place. It was used by the Inuinnait (Copper Inuits) from 1600 – 1900 AD. Around 500 Muskoxen and some Caribou were killed there in this period. There are many tent rings, meat cache, drying arrangements for meat etc on that specific hill.

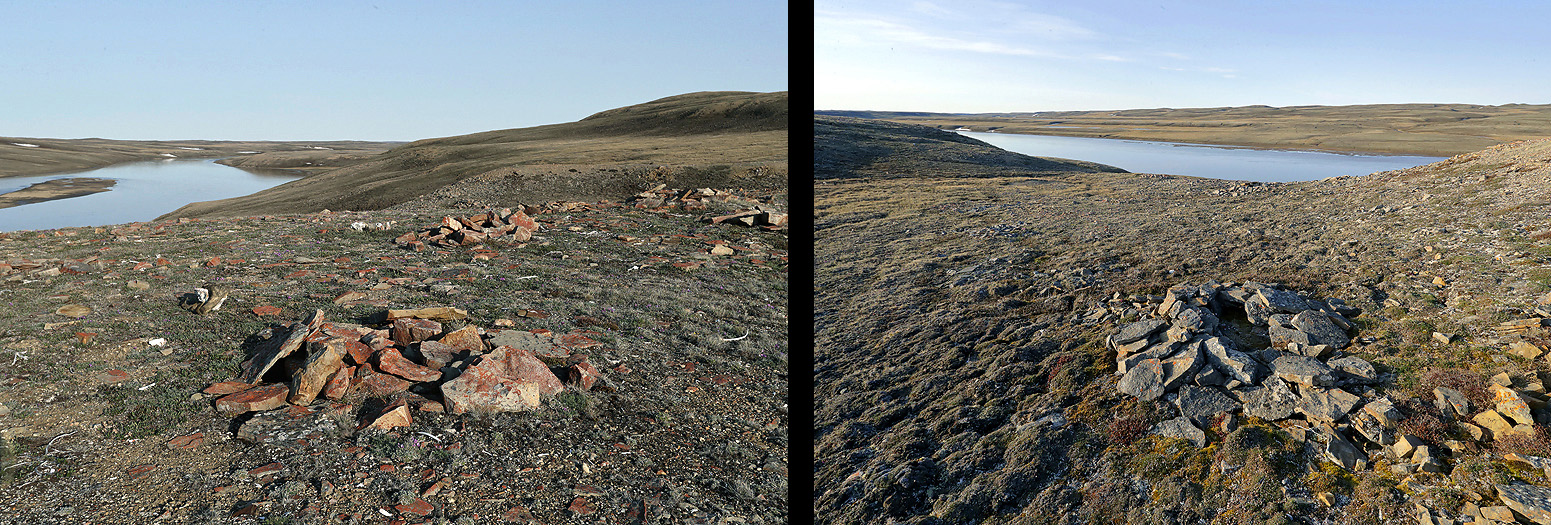

Tent ring at the Naquk kill-site, -note the stone pavement inside, which is for food preparation and is typical on Inuinnait tent rings on Banks Island (left photo). Just beside there was a cluster of man-splitted bones, -which was done to get hold of the marrow (either for eating or used in a lamp), (right photo).

The Inuinnaits led the Muskoxen up to the hilltops where they, as usual, turned and went into a defensive position. The inuit dogs kept them at the place. The hunters shot them with arrows fitted with copper and iron heads. The arrow shafts were carefully selected willow sticks and tied together with sinews. Today (see photo) we find the little arrow hole in shoulder blade after shoulder blade, at an angle showing that the arrow went straight to the heart. The inuits had accurate knowledge of the animal’s anatomy.

The Muskoxen was cut up where they was killed and camp was set up (see tent rings).

From such camps it is assumed that small groups of inuits went back and forth to HMS Investigator in Mercy Bay to collected iron (see photo further down in this post) and wood from the ship stranded in 1851 and abandoned in 1853. This same camps was used year after year, and Muskox skeletons piled up by the camp. Some scientists says this was the reason for the collapse of the Muskox population.

A broken Buckle (mounting), 5 cm long, of bone beside one of the tent rings at Naquk kill-site, assumed to be from the Inuinnaits.

There were several nesting places of Peregrine Falcon of the American sub species “Tundrius” in the river valley. This arctic sub species show typically a very light breasted male.

The Peregrine Falcon is considered to be the fastest bird in the world. For more Peregrine Falcon images, -please see the Peregrine Falcon gallery.

The amount and different species of wading birds was relative sparse.

Ruddy Turnstone (sub species “Morinella”) to the left, and nesting Semipalmated Plover (right).

The Buff-breasted Sandpiper is a special species, they have i.e. lekking behavior as the Ruff. The population has been severe reduced where loss and degradation of its spesialized grassland habitat, both on its wintering grounds in South America and along its migration routes, are believed to pose significant threats.

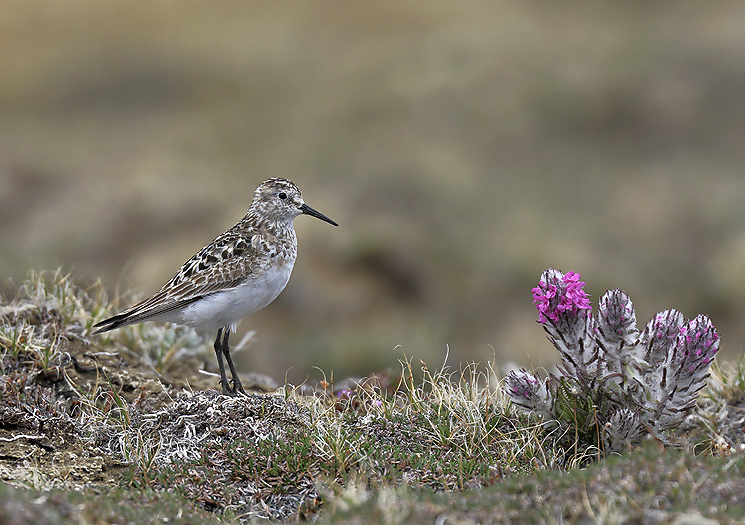

Baird`s Sandpiper at nesting place. For more New images of Waders, -please see the Waders gallery.

As mentioned earlier in this post this river valley has been used by ancient inuit cultures for thousands of years. This caused by the fertile areas with plenty of game along the river valley. It is not known which animals that was the main food source for the people at the oldest inhabited period (Pre-Dorset), but for the latter cultures (Thule and the Copper Inuits) it has definitely been the Muskoxen who attracted them to this place.

On the photo we can see the remains of a tent ring from the Pre-Dorset people who came to this island around 3500 years ago (the tent ring stones have been deliberately highlighted in the photo). These people represents the first human occupation of Arctic North America and may have crossed the Bering Strait from Siberia and then spread rapidly across Arctic Canada and Greenland.

From a more ordinary archeological site than the kill-siste at Naquk

Copper inuit tent ring, typical on an elevated hight above the Thomsen River.

Meat caches (left) and stone Fox trap (right). All dating back to Copper inuit periode from 1600 – 1900 AD.

A piece of iron (8 cm in length) that once probably was collected by the Copper inuits from the HMS Investigator in Mercy Bay after it was abandoned there in 1853 (look closely on the top of the rock in the foreground of the photo). For more new images of Archaeological sites, -please see the Archaeological sites gallery.

We deliberately ended the trip around 10km before the seashore of McClure Strait. This to avoid unwanted confrontations with Polar Bears.

And just as planned, -the Twin Otter picked us up for transport back to the mainland.

Per Michelsen